The point of this exercise is to demonstrate the way we make decisions and the rules of thumb or heuristics that we employ--often subconsciously--whenever we face situations with only incomplete or imperfect information.

Nine have dared face the challenge. Let's see how these brave souls have fared.

1. A town has two schools: one large and one small. Assuming there is an equal number of boys and girls born every year in the Philippines, which school is more likely to have close to 50 percent girls and 50 percent boys born on any given day?

A. The larger

B. The smaller

C. About the same (say, within 5 percent of each other)

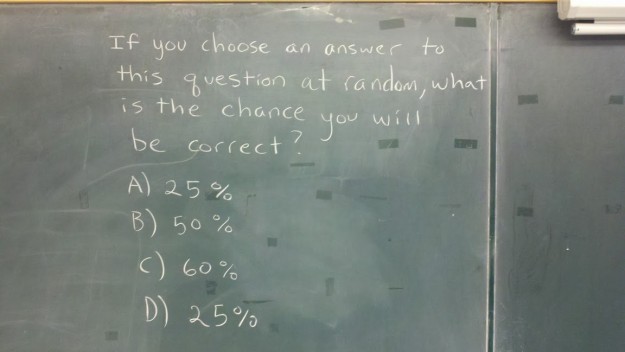

The obvious answer is C since, by intuition, the size of the school should not matter much, if at all. However, if we recall our college or high school statistics, the size of the sample does matter: the bigger the sample is, the more likely our estimate is closer to the actual value (more specifically,

the variance of all possible estimates is inversely proportional to the sample size); therefore, the correct answer is A (6 of 9). The infuriating thing about statistics is that important relationships like this don't make a lot of sense at first glance, so are easily taken for granted by people, especially in real world situations.

2. A team of psychologists performed personality tests on 100 professionals, of which 30 were engineers and 70 were lawyers. Brief descriptions were written for each subject. The following is a sample of one of the resulting descriptions:

Juan is a 45-year-old man. He is married and has four children. He is generally conservative, careful, and ambitious. He shows no interest in political and social issues and spends most of his free time on his many hobbies, which include home carpentry, sailing, and mathematics.

What is the probability that Jack is one of the 30 engineers?

A. 10–40 percent

B. 40–60 percent

C. 60–80 percent

D. 80–100 percent

Since 30 out of the 100 professionals that were interviewed are engineers, the probability that Jack is an engineer is 30%, so the correct answer is A (5 of 9). The reason why some people would think of a higher probability is that they associate the characteristics mentioned in the given description--like being interested in carpentry, sailing, and mathematics--to being an engineer, even if no actual data supports such an association. This rule of thumb is called the

representativeness heuristic.

3a. How many dates did you have last month?

A. 1–3

B. 3–5

C. 0

3b. On a scale of 1 to 5, how happy are you these days (5 being the happiest)?

A. 1

B. 2

C. 3

D. 4

E. 5

It should be obvious that this one doesn't have a correct answer; the point of these two questions is to demonstrate that the first question can easily influence our answer to the next. From the answers of our respondents, we see that a higher number of dates in 3a would likely lead to greater happiness in 3b, and vice versa. However, if the order of the questions were reversed, it's highly likely that responses to the happiness question would have little correlation with the dating question. This demonstrates that how questions or alternatives are presented do affect decision making, even if decision theory tells us that they should not. This phenomenon is referred to as the

framing effect.

4. Imagine that you decided to see a play and you paid 500 pesos for the admission price of one ticket. As you enter the theater, you discover that you have lost the ticket. The theater keeps no record of ticket purchasers, so the ticket cannot be recovered. Would you pay 500 pesos for another ticket to the play?

A. Yes

B. No

This question demonstrates two important concepts in decision making. The first is the concept of the

sunk cost:

that is, past, irrecoverable costs should be irrelevant in decision making. In this situation, the lost ticket would definitely qualify as a sunk cost, so if one really wants to watch the play, then one should not hesitate to pay for another ticket, an alternative which most of our respondents have chosen (6 of 9). However, to a great degree the answer to the question is a matter of personal choice, so there really isn't a correct answer to this question.

We can also use the question to illustrate how framing works. Experiments show that most people would actually choose not to buy a ticket, an indication that people do consider sunk costs in making decisions. If you answered "no" to the question, then consider this analogous scenario:

Imagine that you decide to see a play and you will pay 500 pesos for the admission price of one ticket at the door. As you enter the theater, you discover that you have lost a 500 peso bill. Would you still pay 500 peso for a ticket to the play?

Experiments show that people who answer "no" to the first question would often answer "yes" to the second; this does not make a lot of sense since the two situations are the same and represent the same economic loss of 500 pesos, albeit expressed or

framed differently. It's like agreeing to buy a glass that's half-full for a certain price, then refusing to buy a half-empty glass for the same price.

5a. Choose between getting 9,000 pesos for sure or a 90 percent chance of getting 10,000 pesos.

A. Getting 9,000

B. 90 percent chance of getting 10,000

5b. Choose between losing 9,000 for sure or a 90 percent chance of losing 10,000.

A. Losing 9,000

B. 90 percent chance of losing 10,000

Again, these two questions have no definite correct answer, but are used to demonstrate that people often weigh gains and losses differently. Actual experimental data (I have actually always asked my finance students to answer these two questions) show that respondents tend to answer A and then B (7 out of 9 of you did :)); this result is anomalous since choosing A in the first question is a sign of risk aversion while choosing B in the second question is indicative of risk-seeking behavior. In other words, we can't simply classify decision makers as being "risk averse" or "risk seeking," as traditional decision theory tells us, since individuals can easily avoid risk in a particular situation, then seek it in another, or vice versa. This phenomenon is referred to as

prospect theory.

These questions come from a

Vanity Fair feature on Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman who, together with Amos Tversky, paved the way for behavioral finance/economics/decision making into becoming popular fields of academic research and pretty much debunked the myth of the rational decision maker and the economic theories that are based on this assumption.

Next week, we'll talk more about the heuristics and anomalies that we talked about in this post, and a few others that we have not covered.

It's not enough to just know how people

should make decisions: it pays to also know how people actually do.